Each month when I sit down to write this column, I have the same goal. To empower each and everyone of us to create beautiful trees. Sometimes that entails talking about bonsai philosophically, and at other times we cover specific techniques. My intent to make all of the principles apply as broadly as possible, so we can learn to cook. Cooking? What does that have to dowith it? Have you ever seen some of the cooking shows like Chopped? Contestants are presented with a basket of obscure and oddly paired ingredients that they must take and make into an award-winning dish. There are no recipes, and they can add ingredients. The main requirement is that they transform the ingredients into something different. This means relating the ingredients to each other and thinking about how they might compliment the dish. In my parlance, this is cooking, and not merely following a recipe. Relying on recipes is what I have done most of my bonsai life, and I had some quite tasty ones. But now I am to the point where I need to think on my own. Case in point. I have been growing Douglas Firs for about ten years now. The Artisan’s Cup presented the first Doug Fir I have seen on display. No one has been doing them, yet I have to figure it out. I have had to observe, experiment, regroup, and forge ahead. That is how you create art and that is how we learn to cook. We take what we already know and synthesize it with something new. So that is what I was up to last month with the year-long Growth Chart and Attributes Chart for the pines. Here is what we know, now can we apply this knowledge to other species, or refine what we know? So for this month’s column, I thought I would recap, review, and extend a few of the concepts that I shared in, ‘Everything’s Going To Be Just Pine,’ at last month’s meeting.

We started with a broad approach to pines. We talked about the energy level of different species throughout the year and how that can guide us in the techniques we use and the timing to apply them. Higher energy pines, like Japanese Black, and to a slightly lesser degree Red Pines are described as Double Flush, or Coastal species. Both are two needle pines. These trees produce an excess of energy which leads to long needles and leggy extension of shoots. To manage this energy to our advantage, we decandle the trees in mid-year, forcing it to regrow, or reboot as it were, to produce shorter needles and internodes. This process shifts the fall work calendar for these species. We have to wait longer for the new needles to harden off so that we can work on them – usually October.

By contrast, lower energy pines are often described as Single Flush, Alpine, or Mountain species and would include all of the five-needled or white pines, Mugo and Lodgepole pines, Ponderosas, and just about anything other than the Japanese Black and Red Pines. We use all of the energy that these trees produce during the year. We manage water and fertilizer to keep growth in check, and pinch candles rather than wholesale cutting. That means that we can start working on them as early as August.

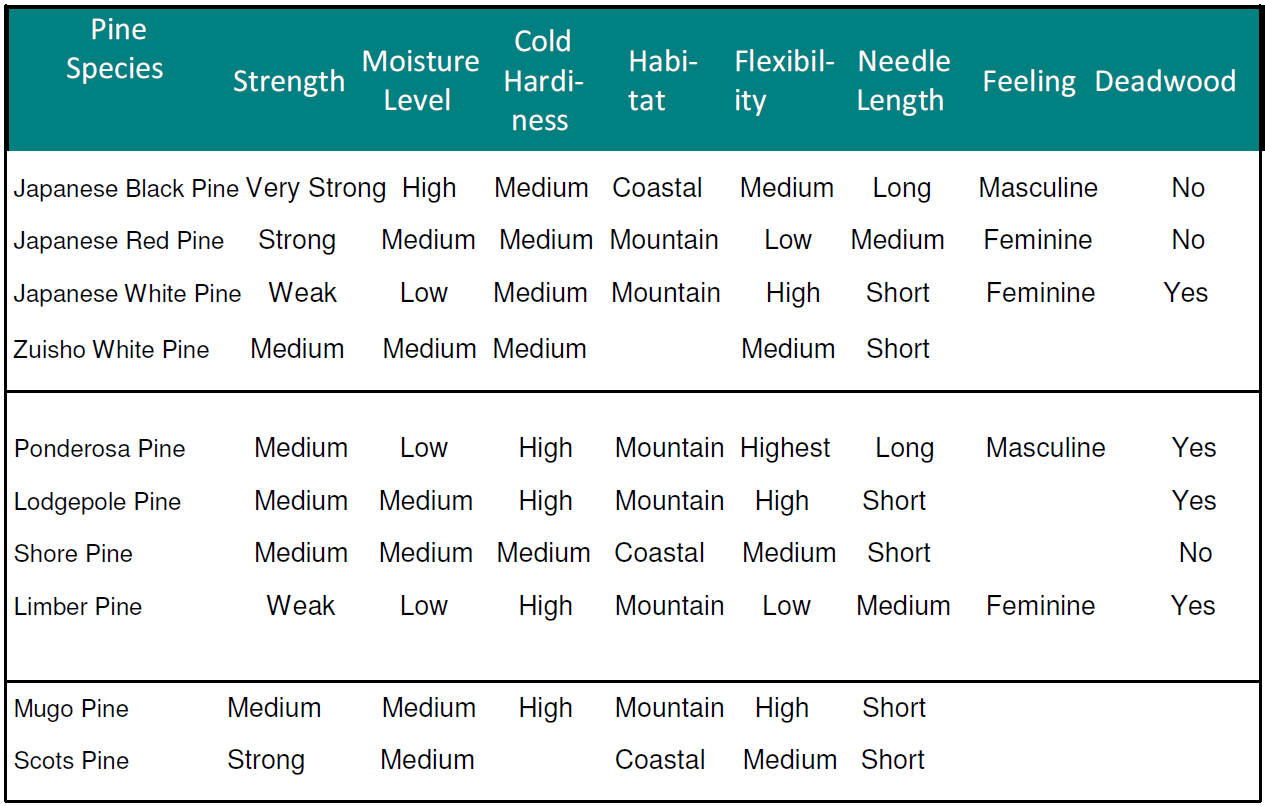

All of the pines species have distinct attributes and we should be prepared to take advantage of what each has to offer, and learn to deal with any disadvantages they posses. For instance, we know that black pines grow really fast, which is great when we want to grow a trunk, and not so good when we want to keep it exactly as is. We can take the sure knowledge we have for one species and apply that technique and knowledge to species with similar properties.

Maybe we can apply what we know about Japanese White Pine to similar species here like Limber Pine. Or maybe we can treat Mugo, Lodgepole, and Scots Pines similarly, even though they are from different continents. I have yet to find the person with extensive experience with all of these different species. So with that in mind, I put together a chart to help relate these different attributes in different species to one another. This is based mostly on my own experiences and what I have gathered from others. I have a good amount of experience with Japanese Black, Red, and White Pines, along with our own native Lodgepole and Ponderosas, but not a lot beyond that.

Take a look at the attached chart and see if you can use it for your own work. If I have left a space empty, I really don’t have much info for you. Better to say I don’t know than to give you incorrect information. Of course, this assumes a healthy and vibrant specimen. Unhealthy trees are very unpredictable, except that they will not follow the rules! There are certainly more columns that could be added, like bark texture, heat resistance, etc… But at least this will point you in the right direction.

And now, few points to remember as we firmly land in fall and gear up for the winter months. This is a great time to work on pines. Actually, we are a little past. So if you do some extreme bending, or thinning of the trees, be sure to give them some winter protection. If you are not sure, leave more foliage, as this will leave more solar collectors operating all winter and help to buffer the challenges of winter.

Other than that, clean out old, withering needles, but be sure to leave some of last year’s needles on each branch. They will continue to produce hormones that help the tree know what to do. Whenever you wire a branch, make sure that both the needles and the buds point up. That will keep them healthy.

The work that you do now on any tree to wire and organize the branches will set the tree up for a successful growing season next year. Without this work, the tree can never really progress as a bonsai. It will not automatically begin to ramify and back bud on it’s own. We have to help. And that is what bonsai is all about, helping a tree be all it can be.

Scott